When Wealth Stops Circulating

Why do capable, well-resourced systems feel persistently tight — even when they appear successful?

This is a diagnostic essay about a shift from scarcity to misallocation, and what happens when wealth stops circulating and begins compensating instead. It is not a guide or a critique, but an attempt to name a structural condition increasingly visible across economies, organizations, and individual lives.

You can expect to leave with sharper questions about:

why effort no longer produces proportional freedom

where capacity quietly compensates instead of flowing

and what “wealth” actually means under conditions of complexity

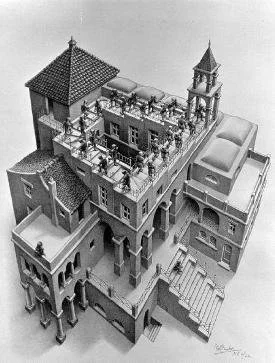

Ascending and Descending, M.C. Escher, lithograph, 1960

The end of scarcity as the central problem

For most of modern history, wealth has been understood as a problem of accumulation.

Nations sought growth. Firms sought scale. Individuals sought income, assets, and security. Scarcity defined the landscape, and accumulation was the rational response. Economic theory, management practice, and personal finance converged around a single imperative: acquire more resources to stabilize the future.

That logic shaped not only markets, but lives.

Today, however, a different pattern is emerging. Across advanced economies and high-capacity populations, the dominant tension is no longer a lack of wealth, but a failure of wealth to translate into ease, resilience, or felt sovereignty. Capital exists. Capability exists. And yet pressure persists.

This is not a paradox of psychology. It is a systemic signal.

When old metaphors no longer hold

The frameworks we still rely on were designed for a different era.

Balance assumes symmetry and stability: distribute resources evenly and the system will hold. Optimization assumes linear leverage: refine inputs and outputs will improve. Both models work under conditions of relative simplicity, where boundaries are clear and cause and effect remains legible.

But contemporary systems — economic, organizational, and personal — no longer behave this way. They are dense, overlapping, and recursive. In such environments, balance becomes arbitrary and optimization becomes brittle. Effort increases, but return plateaus. Stability is maintained not through flow, but through internal compensation.

When static models are applied to dynamic systems, pressure is the inevitable result.

From scarcity to misallocation

What has changed, fundamentally, is the nature of constraint.

In scarcity-based systems, the primary challenge is access: to capital, opportunity, and protection. In such contexts, accumulation is both necessary and effective. But once a system crosses a certain threshold of capacity, accumulation ceases to be the binding constraint.

The problem shifts from how much to how it moves.

Misallocation replaces scarcity.

Attention concentrates in certain domains regardless of return. Strong components absorb volatility created elsewhere. Redundant effort compensates for structural friction. The system remains functional — often highly so — but at increasing internal cost.

Albert Hirschman warned, in his work on development and progress, that systems frequently rely on hidden mechanisms of compensation to sustain forward motion — mechanisms that delay visible failure while quietly accumulating strain.

This pattern is visible in economies that grow without increasing wellbeing, in organizations that scale while burning out their most capable people, and in individual lives that are outwardly successful yet persistently tight.

The issue is not failure. It is inefficient circulation.

Wealth as flow, not stock

In systems terms, wealth is not a static stock. It is a flow.

Healthy systems differentiate roles among their components. Some elements stabilize. Others amplify. Others absorb shocks. When circulation is coherent, these roles are dynamic and adaptive. When circulation degrades, strong components begin to compensate for weak infrastructure — masking fragility while increasing internal load.

As systems theorist Donella Meadows observed, the most powerful leverage points in complex systems rarely lie in pushing harder on outcomes, but in changing how flows are structured and governed.

At the macro level, circulation failure appears as economies propped up by overextended labor, debt, or natural capital. At the organizational level, it surfaces as cultures reliant on a small number of high performers to hold complexity together. At the individual level, it manifests as lives where time, attention, and vitality are continuously mobilized to maintain coherence.

Circulation failure does not replace questions of power or distribution — it explains why even systems with abundant capital can feel brittle and overburdened.

In all cases, endurance replaces flow.

This is the moment at which wealth stops behaving like wealth — and begins to behave like obligation.

Why this becomes visible now

Why is this pattern surfacing now?

Because complexity has outpaced the tools we use to manage it. The past two decades have produced extraordinary gains in efficiency, connectivity, and optionality. They have also compressed decision cycles, multiplied roles, and eroded buffers. Optimization culture delivered growth, but it did not deliver resilience.

At the same time, systems thinking has matured. We now understand that efficiency is not the same as robustness, that strong components can conceal systemic fragility, and that sustainability depends on circulation rather than control. These insights have reshaped how we think about ecosystems, supply chains, and institutions.

They are only now being applied, belatedly, to wealth itself.

A different diagnostic question

If the central challenge of modern wealth is circulation rather than accumulation, then many familiar questions lose relevance.

The issue is not how to optimize further, nor how to balance competing domains, but how capacity is allowed — or prevented — from moving.

Where does attention concentrate relative to return? Which assets stabilize, and which quietly compensate? Where has endurance replaced flow as the default mode of coherence?

Systems can sustain misallocation for a long time — but they pay for it in fragility, quiet exhaustion, and the erosion of choice.

These are diagnostic questions, not prescriptions. They do not tell us what to do.

They tell us what is happening.

In an era of abundant capacity and rising complexity, the future of wealth may depend less on growth than on whether our systems can relearn how to circulate what they already hold.

Further reading (for those who want to go deeper)

This essay draws on a broader tradition of thinking about systems, flow, and the limits of optimization. For readers interested in exploring these ideas further, the following works offer useful depth and perspective:

Systems & circulation

Donella Meadows — Thinking in Systems A foundational introduction to how complex systems behave, and why changing flows often matters more than pushing outcomes.

Geoffrey West — Scale An exploration of how growth, efficiency, and complexity interact — and why systems often become more fragile as they scale.

Compensation, progress, and hidden strain

Albert O. Hirschman — The Strategy of Economic Development A subtle account of how progress is often sustained by hidden compensatory mechanisms — and why those mechanisms eventually create strain.

Joseph Tainter — The Collapse of Complex Societies A classic analysis of how complexity delivers returns up to a point, after which it begins to impose costs.

Limits of optimization

Herbert A. Simon — “The Architecture of Complexity” A foundational essay on why optimization in complex systems often fails — and why satisficing and structure matter more than maximization.

W. Brian Arthur — Complexity and the Economy Essays on increasing returns, path dependence, and why economic systems don’t behave linearly.

Wealth, growth, and meaning

Karl Polanyi — The Great Transformation A reminder that economic systems are always embedded in social and moral contexts — and that disembedded growth produces strain.

John Maynard Keynes — “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren” A short, prescient essay on what happens when material scarcity ceases to be the dominant problem.